Festival of ‘regenerative’ urbanism

Photography and Regeneration:

A Curatorial Essay

Vera Xia, Lecturer in Design & Urban Technologies, University of Sydney Ian Woodcock, Senior Lecturer in Urbanism, University of Sydney

What does regeneration look like?

Why is regeneration important for urban life?

How can photography participate in regeneration?

Photography trains the eye to notice what is overlooked, to dwell on detail, and to frame possibilities in new ways. More than documentation, it can restore attention, spark dialogue, and build awareness of the fragile, hopeful, and ongoing work of renewal in our cities. To photograph regeneration is, in many ways, to participate in it.

The Festival of Regenerative Urbanism 2025 asks us to consider regeneration as a guiding paradigm for urban life: the active work of restoring, renewing, and revitalising. In an age defined by overlapping crises of climate instability, social inequality and biodiversity loss, regeneration offers a way of thinking and acting that is not only about reducing harm but about creating conditions of care so people and ecosystems can flourish.

The photo competition was judged by a panel including ourselves as curators, together with PIA NSW Emerging Planners, represented by Ms Lauren Daly (PIA Associate, NSW Emerging Planners Co-Convenor) and Mr Sebastian Aguilar (MPIA, NSW Emerging Planners Committee, University Engagement Lead). The panel awarded three finalists and one overall winner, as well as one special prize recognising narrative depth.

We were delighted to receive submissions from undergraduate, postgraduate, and PhD students across a wide range of disciplines: urban planning, urban design, architecture, architectural science, geography, interaction design and electronic arts, and disciplines in arts and social sciences. In line with the competition’s focus on student perspectives, only entries accompanied by a photo statement and submitted by current students were eligible for prizes. We also received remarkable contributions from non-student professional photographers; while not prize-eligible, their creativity and insight are recognised here as part of the broader story of regeneration that photography can reveal.

The photographs submitted to this competition reflect regeneration in its many forms. They framed sites of possibility that extend our notion of the urban, reliant as we have always been on systems that extend increasingly far from our everyday city lives: compost heaps and farms as engines of reciprocity, waterways restored as community lifelines, cultural precincts as places of belonging, ageing agricultural buildings re-purposed for new production, including energy. Collectively, they revealed that regeneration is not a singular phenomenon, but an open constellation of practices and interpretations. Together, the photographs form a mosaic of regenerative possibilities.

The submissions show regeneration as a nuanced and differentiated global dialogue. Photographs came from Sydney and rural New South Wales, but also from Singapore, Kyoto, Lisbon, Amsterdam, and Bangkok. These diverse international snapshots presence regeneration as multi-modal global practices shaped by local cultures, including sub-cultures.

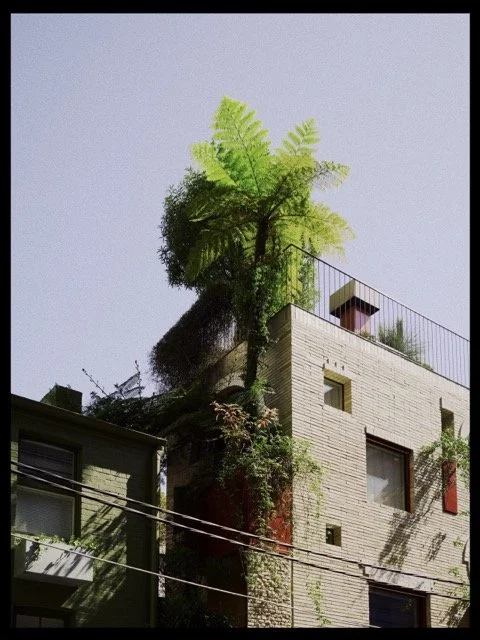

Another striking feature is the breadth, and sometimes wildness, of interpreting regenerative urbanism. Some photographs capture ecological infrastructures (e.g., wetlands, rooftop gardens, vertical facades, hydro power). Others lean towards allegory and poetics, such as a broken clock reclaimed by weeds or a synagogue renovation likened to a butterfly. These diverse images remind us that regeneration is cultural, symbolic, and imaginative as much as it can be about technique.

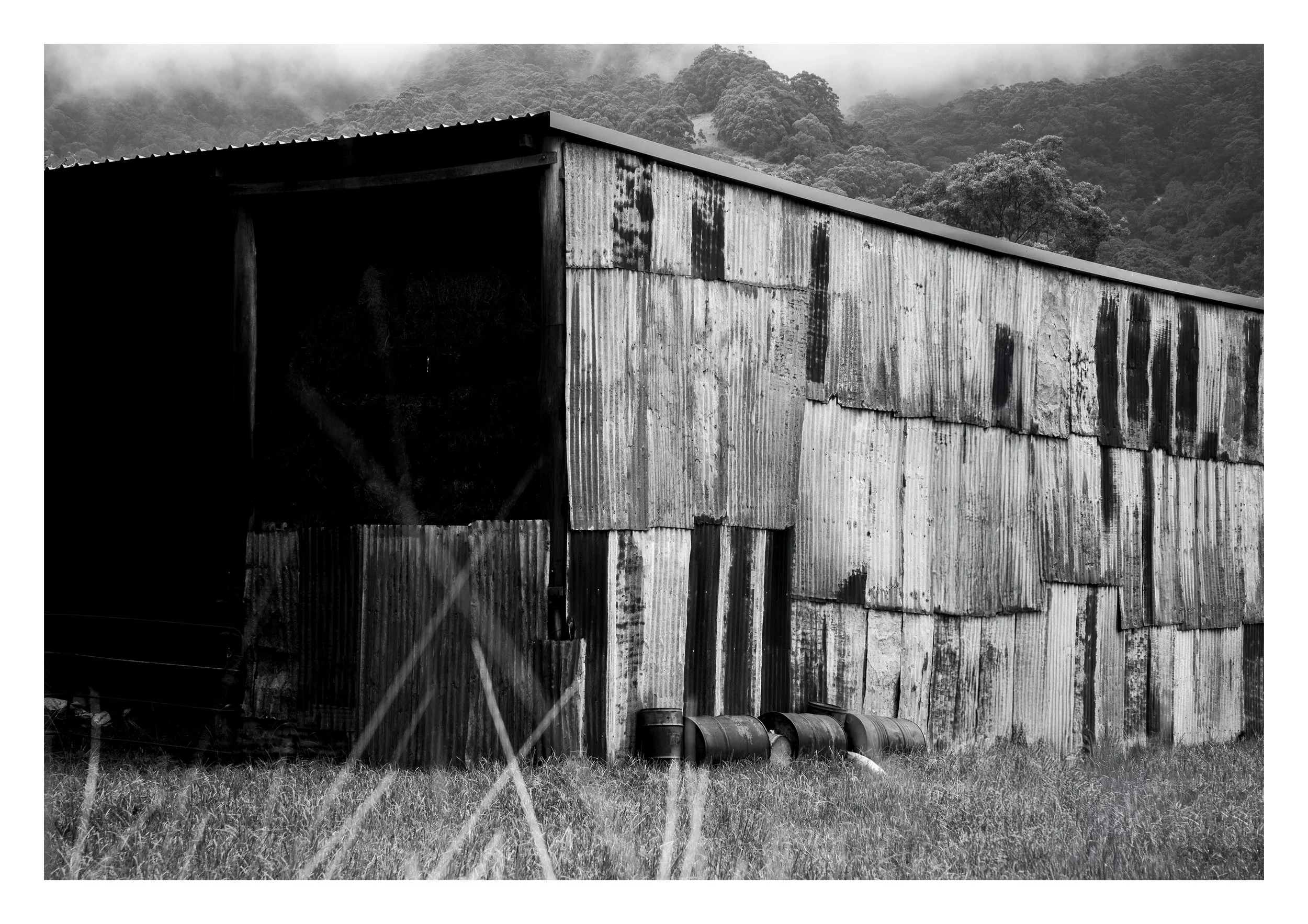

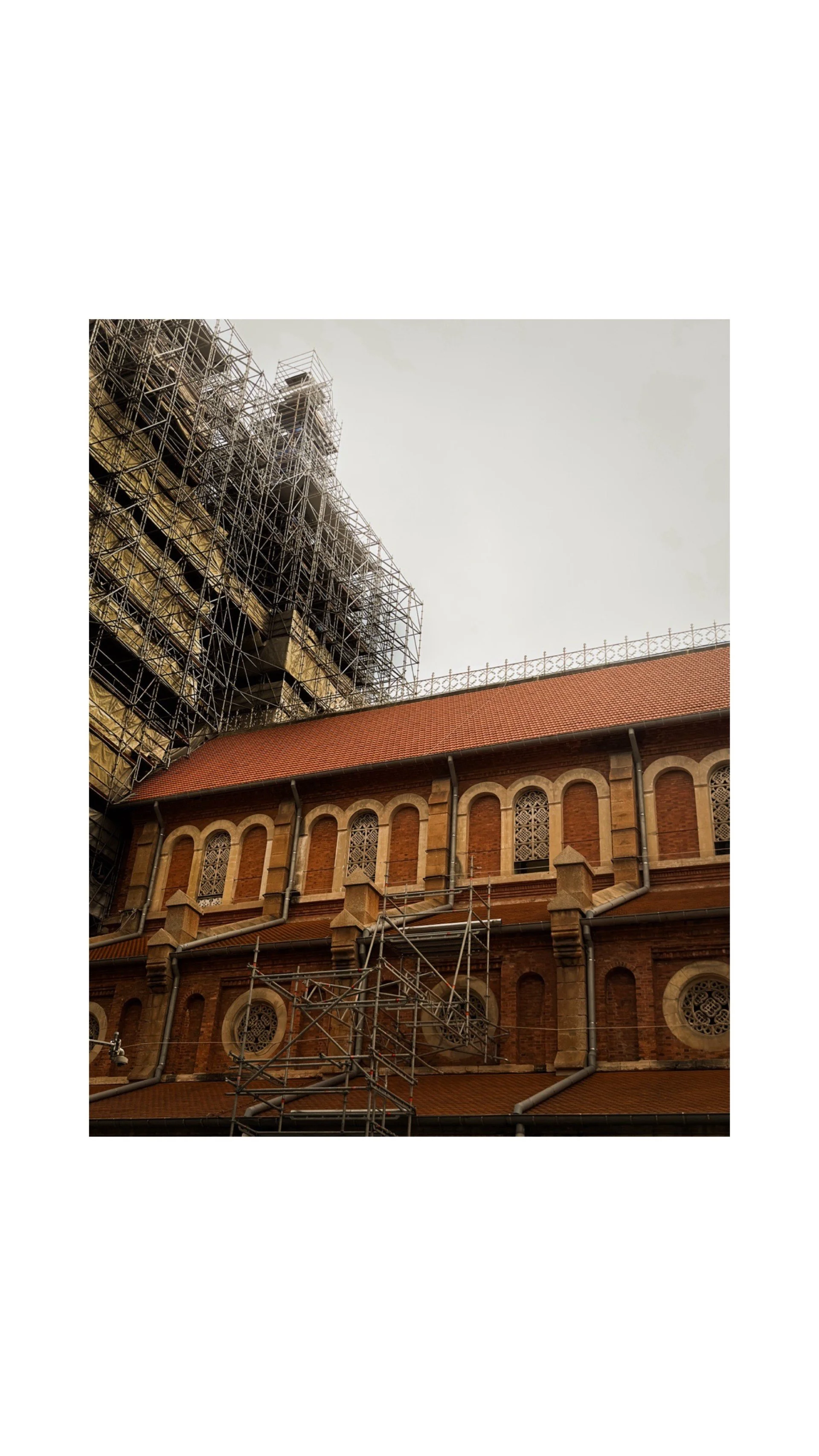

Heritage and continuity also play a strong role. A shrine in Kyoto, a weathered hay shed in Berry, and Naoshima’s glass tea house all show that renewal often begins with care for what already exists. These images suggest regeneration is frequently achieved not through demolition and replacement but through adaptative re-use and reinterpretation, cultural continuity as well as evolution.

A large cluster of entries celebrate green and ecological infrastructure. Sydney’s One Central Park, Barangaroo House, the Drying Green, and Singapore’s Supertrees exemplify biodiversity and ecological systems embedded into architecture and public space. Smaller interventions, such as green laneways or bamboo installations, demonstrate regeneration at multiple scales, from monumental landmarks to intimate, everyday settings.

Equally important are those works highlighting community, labour, and everyday acts of care. Cleaners in Lisbon, re-use economies in Asia, compost bins, dog walkers, and neighbourhood gardens reveal that regeneration is not only a matter of planning or design, but of daily stewardship. These modest yet ubiquitous actions are often the ones that give cities resilience. We can imagine here how a more widespread, active attitude towards connecting with and caring for Country could manifest in a myriad tiny regenerations, everyday, everywhere, to enact the hope embodied in the large, public and highly symbolic projects that are being implemented.

Regenerative urbanism cannot be defined by a single photo. Placed together, these images form a constellation of practices, visions, and stories. Some emphasise resilience, others imagination; some reveal the persistence of nature, others the creativity of communities. Their diversity is precisely what makes regeneration powerful: not a singular model, but a living, evolving practice shaped by many voices. For the students who submitted their work, these images also mark their role as the next generation of built environment professionals, bringing fresh perspectives to urgent challenges.

As researchers, planners, urban designers and lovers of photography, we believe that seeing through the lens is an act of care. As Benjamin famously observed, we experience our cities in states of distraction. Photography has the power to literally capture the flux and flow of our attention through the eyes of the person pointing the camera. Passing moments, fleeting juxtapositions, the minute details that would otherwise be missed - all are caught and held up for considered attention. Often this process relies on intuition and trust in movements of the unconscious, a lot of luck and the right weather (which is often not good weather) and good deal of serendipity. But the taking photographs is fundamentally about curiosity and care – curiosity about the world in all its manifestations and care for the quality of subjective experiences in all their richness and complexity. The photographs we have had the pleasure of curating all demonstrate these traits of a regenerative ethic, and we commend them to you in this spirit and congratulate all participants.

Curated selection

Farmers Market by Gordon Huang

Urban Typologies in the Rural Environment by Charles Boobar

One Central Park by Vicky Halim Maulana

Pipes at Snoqualmie Falls in Seattle by Lillian Lucas

Lilian Zhuang

Huan Feng

Nature’s Canopy Rising Above the City by Akanksha Agarwal

Revival by Ryan Hartley

Heritage, Nature, and Everyday Regeneration by Qingyue Gong

The Berry Hay Shed by Claudia Drinnan

Frank Yang

Sustainable cities: built by humans, like gods by Viran Maddumage

Pasha Grata Putrarinsi

Through Flow, Trace, and Renewal by Jiaqi Chen

Plant a seed by Natalie Yeung

Nature Governs the City by Alana Pittard

A Passage of Light, Bamboo, and City by Vinayak Vikas Khare

Conversion at the Synagogue by Julian Richardson

Kristina Kleine Butron

Laneways Alive: Nature Rooted in the City by Michelle Cheung